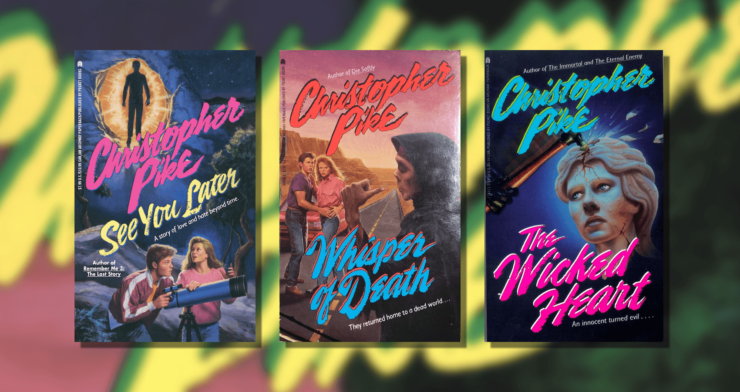

Teen horror of the ‘90s has dangers aplenty: there are human enemies and supernatural monsters, mistaken identity and elaborate faked-death schemes, and all the stress and intrigue of just trying to get through the day as a regular high school student. But in the world of Christopher Pike, that barely scratches the surface, as characters regularly find themselves contending with the lingering evils of the past, visitors from the future (both malevolent and well-meaning), the depths of the cosmos, and complex spirituality. Three of Pike’s novels that tackle some of these thorny issues are See You Later (1990), Whisper of Death (1991), and The Wicked Heart (1993), though there are several others addressed in previous columns that are part of this larger discussion as well, including Chain Letter 2: The Ancient Evil (1992), Road to Nowhere (1993), The Eternal Enemy (1993), The Immortal (1993), and the Last Vampire series (1994-2013).

In Pike’s universe, the past is never really past, with echoes of evil that carry down through the years, influencing and shaping the events of the present.

In the Last Vampire series, Sita recalls her past in ancient Egypt and India, memories that inform who she has become, as well as her interpersonal and spiritual experiences of the worlds she navigates as an immortal. In both The Immortal and The Wicked Heart, the influence of the past is externalized, with dangerous powers reaching across the intervening years to influence the daily lives of contemporary teens. The Immortal’s Josie Goodwin finds herself tapping into the memories of an ancient Greek goddess named Sryope when she visits Mykonos (with predictably disastrous results), while The Wicked Heart’s Dusty Shame is influenced by more recent history, as he is plagued by the voice of a long-dead Nazi, who compels him to kill.

The realities of World War II and the concentration camps are horrifying enough, but in The Wicked Heart, Pike adds a supernatural element through the undying influence of a woman named Olga Scheimer. High school students Sheila Hardholt and Matt Jaye are unofficially assisting Lieutenant Black of the LAPD as he looks into the murders of five young women, one of whom was their classmate Nancy Bardella, when they go to interview a retired police detective, Captain Gossick. Black is overwhelmed by the obvious serial killer case he finds himself trying to solve and Sheila is really pushy about getting answers, badgering Black for information (which he gives her without too much hesitation) and questioning the family members of the previous victims to see if she can find any links or patterns that Black and the police may have missed. Sheila’s the one who figures out that the killer is using online chat rooms to find his victims, with the exception of Nancy, from which she surmises that the killer must have known Nancy in real life, narrowing their suspect search field considerably. Black’s happy for any help he can get and since Sheila’s amateur sleuthing has yielded results, he asks her to keep it up, sending her to talk to Gossick. (Matt’s actually kind of useless, but Sheila brings him along because he recently broke up with her, she misses him, and she’s trying to win him back. This plan actually works in the long run, which is too bad, because Sheila’s narrative closure ends up reducing her to a lovesick girl pining over a boy who doesn’t deserve her instead of a smart and resourceful young woman who helped solve a series of murders).

Gossick tells them of his experiences in World War II, including his chilling meeting with Heinrich Himmler and Olga Scheimer, who he refers to as “Empty shells … I don’t believe there was anything inside them, no soul as we call it. I believe they were simply vehicles for a greater power to work through, an intensely evil power” (147). Following this encounter, Scheimer evaded authorities and fled Germany with her child, a young girl, only to reappear in Los Angeles, where Gossick became a policeman after the war. Scheimer killed six young women in Los Angeles, a pattern that the contemporary murders now echo. Dusty is unaware of Scheimer’s murders and influence, knowing only that a relentlessly hectoring voice commands him to kill, punishing him and threatening to drive him mad if he fails to obey. He uses an online chat system to identify innocent young women and find out when they’re going to be home alone, then breaks into their homes, kills them with a hammer to the head (most of the time—one murder goes awry and ends with a very messy stabbing), then takes the bodies to bury in a cave in the desert, leaving no clues behind with the exception of a small card bearing the image of a swastika.

Gossick tells Sheila and Matt the story of his LA encounter with Scheimer: he confronted her with his knowledge of her crimes, she attacked him, and he shot and killed her, burying her body in the desert and temporarily taking custody of her child, even changing the girl’s name from Sonia to Tania in an attempt to distance the child from her mother’s influence. (Gossick was speaking to Scheimer as part of a murder investigation and shot her in self-defense, so it’s unclear why he felt the need to go rogue in the aftermath, but either way “Strings were pulled. I was dismissed from the force, but I was not sent to jail … I had done what I knew was the right thing. I couldn’t complain about the consequences of my actions” [178]). The consequences for Sonia/Tania continue to reverberate through the years, however: after a brief stay with Gossick, she is removed from his custody and placed with foster parents, who later die by murder-suicide. Gossick loses track of her after that and she remains under the radar, presumably keeping any violent impulses in check, until she is afflicted with early-onset Alzheimer’s and is no longer able to control the subconscious manifestations of her mother’s influence, using that long-silenced voice to compel her son—Dusty, of course—to kill.

In the book’s final showdown, Sheila and Matt go head to head with Dusty in the cave in the desert where he has buried the bodies of his previous victims, as they work to rescue Lieutenant Black’s daughter, Dixie, who Dusty has taken hostage. With five girls murdered, Sheila subverts the voice’s demand for six innocent victims, convincing Dusty that he himself is innocent because “The voice made you do it … You see, then, you aren’t responsible for what you did” (238). This somewhat problematic rationale is coupled with Dusty’s isolation and belief that no one cares about him, leading to his suicide.This brings the latest cycle of murders to a close. However, while Dixie, Sheila and the others walk away from the cave, there’s no real reassurance that another act of senseless violence—whether supernaturally influenced or all too human—isn’t right around the corner. That’s the thing about the dark legacy of the past: it never stays buried for very long and there’s always the possibility that it can reach into the present with horrifying results.

While the past is at least a known quantity, whether from one’s own past life memories or historical record, Pike’s characters are also plagued by complications from the future. In Whisper of Death, Roxanne Wells and a small group of other teens seem to experience a future in which everyone else in the world has disappeared and their own violent deaths are foretold (but more on that later). See You Later’s Mark Forum is on the flip side of that scenario, just a ‘90s guy living his life when a couple of people show up from the future and turn everything upside down. It turns out that the future beings, Vincent and Kara, are versions of Mark himself, and Becky, the girl from the record store down the street he has been crushing on. She’s dating a real jerk of a guy named Ray, who also comes back from the future, as Frederick, to complicate things further. In the timeline from which Kara and Frederick have returned, Frederick is largely responsible for World War III and the end of life as we know it, using his status as a high-ranking general to launch nuclear warheads and blast most of the planet to smithereens from his protected position on a space station. However, trapped on the space station with limited resources, no liveable home planet to return to, and no other civilization to appeal to for help, everyone on the space station, including Kara and Frederick, asphyxiate and die … or would have if they were not rescued by the Illumni, who Kara and the others see as disembodied light sources outside the space station windows. These beings radiate peace and usher the individuals on the space station to a kind of remade Earth-bound Eden, an unspoiled paradise. These celestial beings of pure light make Kara an offer that could change everything, to “go back to any point in our lives for exactly one lunar cycle—approximately one month—and try to change the course of our lives in such a way that the history of the world would also be changed” (132). The only way she can think of doing so is by following “the direction of love” (133), going back to the point in her history where she chose the relationship she had with Ray over the possibility of a life with Mark.

As with just about any time travel narrative, however, it’s not that easy. Frederick doesn’t really want things to change– he has no regrets about the destructive choices he made, or their impact on the world or humanity at large. Frederick and Kara hate one another, an animosity that follows them back from the future and makes any real meaningful dialogue or compromise almost impossible. Future Kara tries to sabotage Present Becky’s relationship with Ray, in an attempt to create a new path forward, though Mark’s misgivings, Ray’s anger, and Becky’s sense of outraged betrayal are inevitable roadblocks to this plan, and when Kara has no choice but to tell Mark the truth, he unsurprisingly finds it difficult to believe.

None of it ends quite the way any of them had planned: instead of a new life of love between Becky and Mark that could potentially change the course of human existence, the conflict between these past and future selves instead becomes a battle to the death. Frederick kidnaps and kills Vincent, but not before Mark has the opportunity to inhabit Vincent’s body, see through his idealized future self’s eyes, and (sort of) survive his own future death as his disembodied present self. Kara attempts to kill Ray, but ends up killing Becky instead when Becky tries to save Ray, who then shoots Kara with a gun Frederick gave him, in the hopes that a confrontation like this might give him the chance to have Kara removed from the equation altogether. Instead of rewriting the future through a new and more hopeful love, the path to a new future detours through Ray’s tragic loss of Becky, as he is overcome by a grief that just may steer him away from violence in the years to come. That’s their goal anyway, as Frederick and Kara attempt to work through Ray and Becky in these final moments, as they end their own parallel stories reconciled to the love they once felt for one another in those long-past days.

The final moments of Frederick and Kara’s stories are pretty complicated too. Mark’s assumption has been that the Illumni brought these travelers to the present through a time machine concealed in the cave behind Vincent and Kara’s house and that when the time comes, they will pass back through that time machine to the (hopefully transformed) future that awaits them. While Kara has told Mark that the Illumni are radiant alien beings capable of time travel, when he reflects on the stories she told him and his own experience with the bright light he saw in the cave, he comes to think of the Illumni as angels of a sort, with the white lights echoing that of near-death experiences and humanity’s visions of heaven. But in the end, he decides the Illumni are even more wondrous, asking “If one version of our future selves could come back in time, why couldn’t an even more distant future version also come back? … Who were the Illumni? I think they were ourselves” (222). This adds an additional dimension, another future in which humanity—or at least individual humans—achieve transcendent enlightenment, elevated to a higher plane in which they become their own angels, their own source of salvation.

Mark’s consideration of this complex spirituality is echoed throughout much of Pike’s larger body of work as well. The Last Vampire’s Sita has an extended and intimate friendship with Krishna and is well aware of realms beyond the here and now, while in Chain Letter 2: The Ancient Evil, if the characters fail to follow the Caretaker’s demands, they’ll find themselves in a hellish box of eternal purgatory and damnation. In The Wicked Heart, Gossick practices a kind of transcendental meditation (which actually parallels some of Sita’s experiences in the Last Vampire series) after studying with Rabbi Levitz, whom he met during the liberation of Dachau. Rabbi Levitz is able to read minds and move objects telekinetically, feats that Gossick says “open[ed] my mind up to possibilities I had not considered before” (148). When he asks Rabbi Levitz to teach him, the rabbi tells Gossick that all he has to do is quiet his mind and open himself up, to be “available to the power of the universe” (149). This meditation does not come easily to Gossick, though when he does attain this state of transcendence, he is able to sense his conflict with Himmler and Scheimer as one between macrocosmic, free-floating powers of immense good and evil, rather than simply an interpersonal, human battle. The spiritual vision of See You Later builds on this wealth of possibilities, incorporating humanity and its potential promise as the path to salvation, that better, future versions of ourselves may become the guiding lights we seek. And in the final pages of Whisper of Death, the barriers between the human and spiritual prove porous as well, when Roxanne becomes aware of and then passes into “a wonderful light, where she saw many rich colors and heard many wonderful sounds … In that moment, Roxanne felt as if she had stepped into the center of all things, where the light of the stars shone bright, and the ending of every story was joyful” (173). As these examples demonstrate, Pike’s representations of spirituality are not bound to a single belief or faith tradition, though they are united in their promise of peace, hope, and a higher power.

Whisper of Death complicates the distinction between visions of the future and individual perception, following a similar narrative pattern to Pike’s Road to Nowhere. While Road to Nowhere is a cautionary tale about rethinking suicide, Whisper of Death is a story about the evils of abortion, which in this case opens the doors to a purgatorial nightmare that ends with Roxane’s death. In Whisper of Death, Roxanne and her boyfriend Paul Pointzel (whom everyone calls Pepper) end up unexpectedly pregnant and while Roxanne wants to keep the baby, Pepper talks her into getting an abortion. They go to a nearby town, but shortly after beginning the procedure, the doctor leaves the room and Roxanne changes her mind, gets up, and leaves. Roxanne doesn’t see the doctor or nurse on her way out and as she and Pepper drive back to their hometown of Salem, they don’t see anyone on the road either, with the exception of a red-haired hitchhiker in the desert that Roxanne glimpses briefly while Pepper is asleep, though even the hitchhiker disappears as the car gets closer. There’s no one at the gas station where they stop to fuel up the car, but it doesn’t get really weird until they make it all the way back to Salem and find that the whole town appears to be deserted. Over the course of the morning, they discover a handful of fellow teens—hot girl Lindsay, loose cannon Helter, and resident nerd Stan—and they get to work trying to figure out what’s happening.

In the end, the horrors all come back to Betty Sue McCormick, a classmate of theirs who committed suicide the month before by setting herself on fire. Betty Sue was a bit of a dark mystery: no one knew her really well, though those who came within her orbit discovered what she was capable of. Lindsay was Betty Sue’s childhood friend, and when Betty Sue used some sort of dark magical power to make Lindsay beautiful, Lindsay left her former friend behind, losing herself in her new identity and popularity. Stan considered himself Betty Sue’s friend, though he also tells Roxanne that he felt like Betty Sue exerted a power over him, calling him to her when she needed or wanted him, having him do tasks for her, and dismissing him when she no longer needed him. Stan also recounts a chilling encounter he had with Betty Sue in her backyard, where she caught several butterflies in glass jars then happily watched them fly around in small circles until they suffocated and died, all under her complete control and watchful gaze. Helter raped Betty Sue, forcing himself on her in one of the school gymnasium’s equipment rooms where he and Betty Sue were making out, refusing to stop when she tells him to; while Helter tells the other teens that Betty Sue had seduced him with her dark power, he does take ownership of his actions and recognize his culpability, aware of how he hurt her and acknowledging what happened as rape. Pepper impregnated Betty Sue, then pressured her to get an abortion, just like he did with Roxanne. Both Helter and Pepper try to absolve themselves of at least some of the responsibility for their actions, telling the others that Betty Sue used her magical influence on both of them, effectively blaming the dead girl for her own violation and abuse, which makes their eventual deaths feel pretty well-deserved.

As the teens talk about Betty Sue, Roxanne realizes that she may have been the mysterious hitchhiker she briefly glimpsed in the desert, and as they make their way around Salem sharing their memories and confessions, they discover that each of them had harmed or failed Betty Sue in some way. In retribution, she wrote vengeful horror stories about each of them, foretelling how they will die. These premonitions begin to come true one after another, through dual timelines: for example, Betty Sue writes of Lindsay being set aflame and in the deserted version of Salem, Lindsay is killed when a car explodes as she’s filling it with gas to make her getaway while smoking a cigarette (even though Lindsay wasn’t ordinarily a smoker), while in the parallel “real” version of Salem that Roxanne and Stan read about in tomorrow’s paper, Lindsay dies when her car explodes as she tops off the gas tank in her garage at home. There are similar stories for each of them, which come to pass as the teens struggle—and fail—to escape.

When Roxanne and Betty Sue are the last two standing, Betty Sue tells Roxanne that she is Roxanne’s aborted child, saying that “I was the one in your womb. I came back for you … But to do that, you had to kill me first” (162). Roxanne and Betty Sue’s narratives diverge here, with Roxanne insisting she didn’t go through with the abortion while Betty Sue’s presence seems to indicate otherwise, and Roxanne finds herself reassessing everything she has seen in Salem and believed to be true. As in Road to Nowhere, where Teresa Chafey is on a long, weird drive with a couple of hitchhikers that ends up being her own internal perception of an escape while her physical body is dying in her bathroom at home in a suicide attempt, in Whisper of Death Roxanne never left the clinic at all: something went wrong during the procedure, she began to hemorrhage, and she died on the table.Everything since she got up and left the clinic has all been a vision of her dying mind.

While (back in the “real world” of the novel) the doctor notes that he has never seen anything like this before and the conversations surrounding abortion through the book are focused on Roxanne knowing her options and making an informed decision rather than moral pressure or judgment, it’s definitely an abortion = death story, which becomes particularly pronounced when the reader learns that both Betty Sue and Roxanne died as a direct result of being pressured into getting an abortion by Pepper’s insistence. In other words, if either of them had made the “right” choice (to not get an abortion), they’d probably still be alive. Pike isn’t ideological or political in his presentation of the fatal consequences of abortion for these two young women, but the stigma and judgment are implicit, and one shudders to think how this might have shaped teen readers’ perceptions of reproductive options and choice.

Roxanne dies in the novel’s final pages, which would seem to negate the horrors that had played out in deserted Salem, but that doesn’t turn out to be the case, as Pepper drives back home, sees a mysterious red-headed hitchhiker bound for Salem, and picks her up. Though he fails to recognize Betty Sue and put two-and-two together, he is “struck by how familiar she looked … there was something he was missing here” (179). The first iteration of the horror may have been all in Roxanne’s mind, but it will certainly continue without her.

The conclusion of Whisper of Death posits a circularity to narrative and experience, a sense of events progressing in an infinite loop rather than reaching a fixed narrative conclusion. The epilogue of Whisper of Death returns readers to the clinic, but in the last full chapter before this epilogue, Roxanne is self-referentially writing the story of the events of Salem, watched over and directed by Betty Sue. The act of storytelling itself is essential here as well, as Roxanne not just records what has happened, but articulates her perspective and reflects on her experience, constructing a cohesive narrative out of the trauma she has endured. This circularity is a feature of Pike’s larger body of work as well, though it carries different meanings, depending on the context. For example, in The Immortal, Pike draws on reincarnation and the synthesis of Josie and Sryope’s souls and experiences to draw the reader back to the beginning, reflecting the timeless nature of legend and the infinite possibilities of reincarnation. Much like the past which is never really put to rest in Pike’s novels, the end of the story is never really the end, but may just loop right back to the beginning.

Christopher Pike’s universe is deeply spiritual and philosophical, providing teen readers with the opportunity to think beyond not just how not to get murdered or who (or what) the enemy might be, to consider the meaning of life, planes of existence and perception beyond the everyday, and the endless possibilities that exist just beyond the “real.” These teens are grappling with conflicts that ask them to look deep within themselves to find out who they are, what they value, and what they’re willing to fight—and even die—for. The stakes are high and even death doesn’t mean the end of the struggle, as Pike provides visions of both peaceful and purgatorial afterlives, as well as transcendent levels of spiritual understanding that supersede them all. Pike’s novels overflow with murder and mysteries, monsters and aliens, capitalizing on the horror trend that had teen readers buying these novels in droves. However, unlike many other authors in the ‘90s teen horror tradition, Pike is confident that his readers are capable of tackling the big philosophical quandaries and asking questions that don’t have any real answers, as they consider how the world works, what lies beyond, and what it all might mean. In Pike’s universe, teens—both characters and readers—are capable of great things and make choices that can change all of human existence and the universe itself. Some of the possibilities may be dark and terrifying, but for those who endure, there’s also the chance for enlightenment and transcendence.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.